Introduction

Within the book “American Fighters in the Foreign Legion” historical interesting first hand accounts of battles fought by the French Foreign Legion during The First World War can be found.

When researching in more detail what actually happened to a group of legionnaires originating from the Netherlands who took part in the attack of the June 16th 1915, the book again proved to be a useful source.

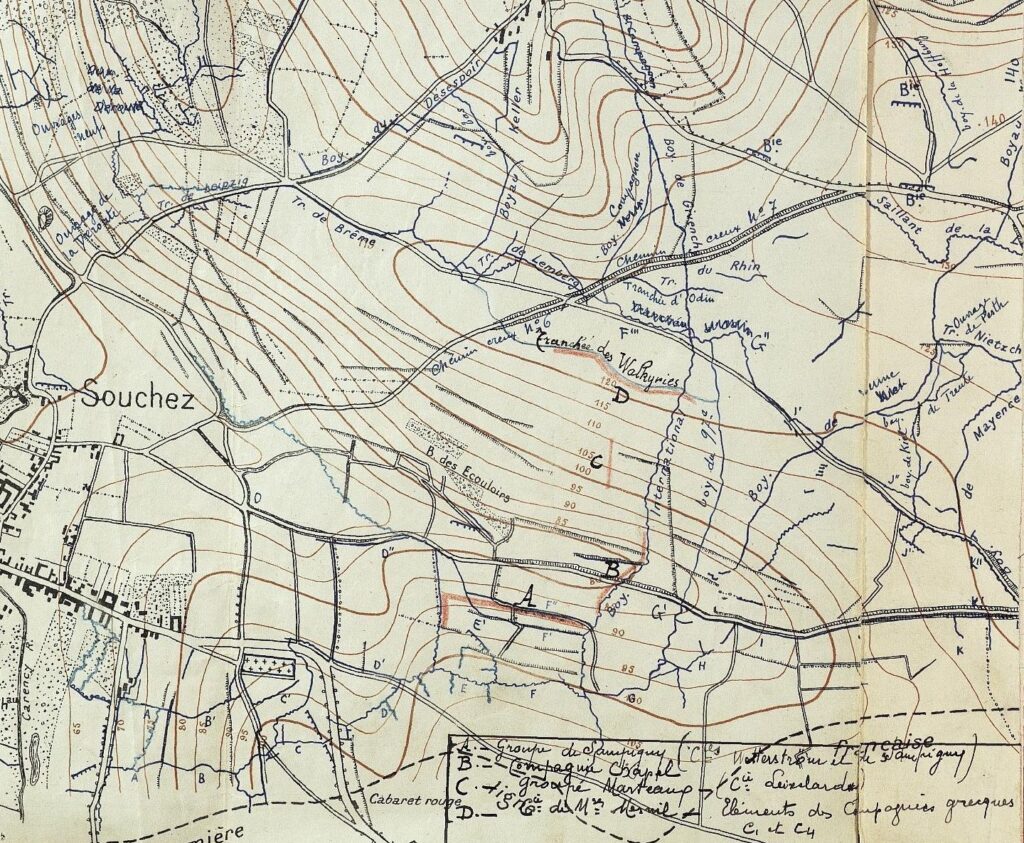

I tried to link the accounts provided, to an interesting map I found in the War Diary of the 2e régiment de marche du 1er régiment étranger.

Unfortunately the legend of the map is given on the basis of the commanders of the various units and not by the Battalion’s as in the book. An attempt will be made to assign the commanders to the specific batallion’s to place both the map and the account in context, but this might take some time.

The accounts.

Early in June, the Legionnaires went into the trenches around Carency, just north of La Targette and Neuville-Saint-Vaast, which they had captured on May 9 1915.

On June 16 1915 they joined in a grand assault directed against the German positions about Souchez, including the powerfully fortified works of the Cabaret Rouge, the ‘Labyrinth,’ and Hill 119.

Paul Pavelka wrote from hospital on June 10 a vivid description of the battle:

The attack commenced at noon on the 16th. It was led by the Moroccan Division, as on the 9th of May.

Battalion B let go first in our sector, facing a most dreadful fire from machine guns, rifles, and shrapnel. The only thing for us to do was to cover the ground as quickly as possible, which we did, reaching the first of the Boche trenches to find they had fallen back to their second line. We took a short rest here rallying, as many of our boys fell on the way over.

The Greeks were behind us, and soon came piling head over heels into the trenches where we were.

Everything was mixed up from now on, as there were two battalions, B and C, in the short space of about three hundred metres.

The next move was even more difficult, for the Germans kept up a most terrible rifle and artillery fire in order to keep the reserve forces from coming up to our aid. But, nevertheless, out of the trenches we climbed, making for line number 1 as quickly as possible.

Here I strayed away from my company, Neamorin and I being together. He soon got a bullet in the side; I laid him

in a marmite hole, and pushed on. How many times I was compelled to lie down I could not say, but eventually I managed to reach that dear old second line of Germany. Some surprise was in store for me, you can bet. As I reached the edge of the trench, I noticed the gray caps of the Bavarians, and almost instantly I felt a stinging pain shoot through my left leg. A Bavarian had stabbed me with his bayonet; he then threw up his hands and yelled ” Kamerad,” but I blew his brains out. I dropped just in front of the trench.

The next was a mix-up of howling and hurrahing, for tirailleurs, the Zouaves, and the Legion were all piling in on them. It was soon over, the Germans getting out and running for their lives to our rear, without arms and nobody stopping them.

I got into the trench now and the rest went on. The blood ran freely from my wound, so I put on the first-aid package. As I lay there I saw many wounded coming in, and ever so many prisoners. I looked out of my trench and saw our boys slowly gaining Hill 119, which was directly in front of me. It was easy to distinguish them, all having white cloths pinned on the back, and no sacks.

A. Groupe de Lampiguy (Cies Wetterstrom et de Lampiguy)

B. Compagnie Chapel; (Cie Leixelard)

C. Groupe de Marteaux

D. Cie des Mre Mesmil Elements des Compagnies greques C1 et C4.

Souchez, Bois des Ecouloirs, Tranchée des Walkyries

I made my way to the rear unaided, and reached the poste de secours, where I got a wagon to Camblin Abbey. There I met Larsen, with his jaw shot away; Zannis the Turk, with his hips torn off by a piece of shell, and others of our company. I heard that the captain was killed, and Kelly and Smith were wounded.

[…]

Frank Musgrave added to Pavelka’s account:

Battalion A, which had suffered most on May 9th 1915, reenforced B and the Greeks. We got out, and advanced slowly for a couple of kilometres, following the attack. B had gone out, and I understand the Greeks refused to go out and we passed and went ahead of them. By night we were almost in touch with the Germans, and were going forward with fixed bayonets.

At daylight on the 17th 1915 we took and held a German trench far in the German territory, and though they tried to shell it down we held it all day. They advanced a battalion at four o’clock in the evening to carry it by storm, but, shelled out of the depression in which they had come up by the seven tyflves, when they broke for the open they had to face such a furious fire from the Legionnaires that they fled for the rear and were exterminated to a man.

We were relieved at daylight the 18th by a French regiment. My battalion losses were not so heavy as May 9th, and mostly caused from shellfire, although the battalion inflicted a good deal of loss on the Boches. But B was hit hard, and when we got back to Mingoville I searched in vain for the Americans The regiment never recovered from that stunt. I never suffered so much from heat, fatigue, thirst, and other breeds of misery as on that occasion.’

The losses of the Legion on June 16 were even more terrific than on May 9. Thinking to avoid loss of life from their own artillery fire, the Legionnaires charged without sacks and with large squares of white cloth sewn on the backs of their coats. The artillery observers were instructed to watch these white squares and to keep the artillery barrage always directed in front of them. Unfortunately, the observers, who were stationed in tree-tops and on roofs, were killed early in the battle, and, as on May 9, hundreds of French soldiers were killed by their own artillery fire.

Germans hidden in deep underground shelters came out after the waves of assault passed and fired on the attackers from behind with machine-guns and rifles. They had tried the same trick on May 9, and on June 16 two men in each squad in the Legion were given long knives and bags of hand grenades and instructed to clear out every shelter where foes might be lurking. Kenneth Weeks was one of the men entrusted with this dangerous mission.

When the first order to leave the trenches was given, the Greeks refused to obey. Colonel Cot, commanding the Legion, rushed over and argued with them, promising that they would be sent to the Dardanelles after the attack, and induced them to join in the charge. A regiment of Algerian tirailleurs advancing behind them probably hastened the decision, but once they got started, the Greeks did brilliant work.

Some sections of Legionnaires got mixed in with the Zouaves and the tirailleurs and helped carry the ‘Labyrinth,’ where some of the fiercest hand-to-hand fighting ever known occurred. The main body, however, stormed Hill 119, successfully carrying the extensive fortifications on the western slopes and the crest.

Several companies broke far through the enemy’s lines at the Cabaret Rouge, but were entirely cut off and surrounded by the Germans. Every man in the detachment is supposed to have fallen, as none was ever heard from again.

The supporting regiments failed to arrive, and nightfall found the greatly depleted band of Legionnaires stubbornly holding on to the crest of Hill 119, repelling counter-attack after counter-attack. The Germans kept up a terrific bombardment throughout the night and the following day, and the Legionnaires supply of ammunition was virtually exhausted and the men dying of thirst and fatigue when relief arrived during the night of July 17.

The roll-cal

Few men answered the roll-call behind the lines.

Harmon Dunn Hall, who had arrived with the reinforcements from Lyon just before the attack, was killed early in the battle. He was one of a machine-gun section, and with his comrades rushed over to a captured German first-line post and set up his piece. The enemy was keeping up an intense fire, and the Legionnaires were poorly sheltered, as what had been the unprotected rear of the trench was now the attacked front. It was necessary to crouch low in order to be safe, but Hall kept putting his head up and looking out to observe the enemy’s movements.

‘ Keep your head down,’ advised a sergeant.

Til not duck my head for any damned Boche,’ replied the American.

A few minutes later a bullet crashed through Hall’s brain.

Near him fell his closest friend in the Legion, Joseph Ben Said, the favorite son of a Moroccan chief.

Kenneth Weeks, Russell Kelly, and John Smith were listed as missing.

Kenneth Weeks, after the battle of May 9, had been put in a squad of Italians, and some of his comrades who turned up later in hospitals reported that the last they saw of him he was dashing towards a machine-gun nest in the German third line, hurling grenades at the foe. Weeks had been cited for coolness and bravery during the storming of La Targette, and proposed for a corporal’s stripes, it being understood that he was to take charge of the American squad.

Kelly and Smith were reported seen in a German second-line trench; Kelly with a bullet through the thigh, and Smith with a bullet in the shoulder. Neither was dangerously hit, but both were too weak from loss of blood to crawl to the rear, as did some of their wounded comrades. The enemy counter-attacked later in the evening, and retook the line where the injured Americans were lying; they were believed to have been massacred, as certain units of the German Army refused to take prisoner any soldier of the Legion.

Lawrence Scanlan was first reported missing, but was later found dangerously wounded. He described his experience as follows:

‘We all left the advanced trench together, but I soon found myself in the Greek battalion, and with it I reached the

first German trench. Some distance away I saw my captain and other Americans and I started over to them. Then machine-gun bullets hit me, smashing my thigh and an ankle. After lying fifty-six hours on the battlefield, I was found by stretcher-bearers and carried to the rear. I have seen none of my com- rades since that time.’

Scanlan was decorated with the Croix de Guerre as he lay in hospital, being the first American volunteer to receive that honor. His citation in Army Orders called him an exceptionally brave Legionnaire, and mentioned his gallant conduct on May 9 and June 16 1915.

L’élève pilote Laurence Scanlan, lui aussi, est l’un des volontaires américains qui semblent préservés de la mort par un sort. J’ai déjà raconté comment il se battit à la Légion étrangère, fut très grièvement blessé à Givenchy le 16 juin 1915, et comment, après avoir été réformé n° 1 avec sa jambe droite plus courte que l’autre de quinze centimètres, il reprit du service – à l’escadrille La Fayette.

[ La Guerre aérienne illustrée Date d’édition : 1917-08-30 ]

Frank Musgrave was the only American in the attack who came through it unscathed, and was henceforth known throughout the Legion as ‘Lucky’ Frank.

Corporal Didier was gravely wounded as he charged a German machine-gun nest, yelling and brandishing his rifle, and the veteran Legionnaire Godin was killed by a bullet through the head.

All the Legion officers taking part in the attack were either killed or wounded and the surviving men were commanded by sergeants and corporals.

Captain Wetterstrom, in whose company were most of the Americans, was killed. He was a Danish officer who had served for several years with the Legion in Morocco, and was one of the few officers untouched during the attack of May 9. His last citation in French Army Orders called him ‘an officer of rare bravery, who gave proof always of a complete contempt for danger.’ The flags over public buildings in Copenhagen were put at half-mast, when the news of Wetterstrom’s death reached Denmark.

The celebrated Russian painter Koniakof was among the slain, as was one of the most unique characters in the entire Legion, a former priest who had been a Legionnaire for twenty years. Whenever he was scolded by an officer, this man would often reply: ‘How can you talk like that to a man who still has the power to make God descend into the Host? I am clothed with a divine character; and I am also a victim of love!’

When he was twenty-five years old, the priest had seduced one of his fair young penitents, and eloped with her. She soon abandoned him, and to forget his sorrow he enlisted in the Legion. His only distraction was reading Latin classics, volumes of which he always carried with him in his sack.

Kenneth Weeks’s body was found between the lines when the French advanced near Souchez in November, 1915. He was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre with a striking citation:

Kenneth Weeks: An American citizen of a high intellectual culture, animated by the most noble sentiments, and having for France a profound admiration. He spontaneously enlisted at the beginning of hostilities, and has given proof of the most brilliant qualities during the campaign, and particularly distinguished himself June 16, 1915, during

an attack against the German positions.

Just before the attack on June 16, John Smith gave to Paul Pavelka an envelope, marked ‘To be opened in case of my death.’ After long inquiry amongst the Legionnaires who survived the battle, including a number of wounded in hospitals, Pavelka and Paul Rockwell were convinced that Smith had been killed, and opened the envelope. It contained a slip of paper on which was written in pencil:

‘Please tell Mrs. James B. Taylor, Wooster, Ohio, that her son Earl is dead.’

Correspondence with his mother revealed the fact that ‘John Smith’s’ real name was John Earl Fike. His family had not heard from him for years. When he volunteered in the Legion, he had taken the name of a grandfather, Captain John Smith, of the Sixty-Second Ohio Volunteers, who fought in the Civil War, not because he had any reason to hide his identity, but because he evidently found it more romantic to fight under the name of a soldier ancestor.

Fike’s body was never found, nor was that of Russell Kelly.

Reference: American Fighters in the Foreign Legion [ p. 81 – p.86 ]

Harmon HALL

Mort pour la France le 16-06-1915 (Souchez, 62 – Pas-de-Calais, France)

Né(e) le/en 19-03-1890 à saint paul (Etats-Unis)

Grade soldat de 2e classe

Unité 2e régiment de marche du 1er régiment étranger

Classe1914 (EV) Bureau de recrutement La Rochelle (17) Matricule au recrutement 293

Russel KELLY

Mort pour la France le 16-06-1915 (Souchez, 62 – Pas-de-Calais, France)

Disparu / Tue au Combat

Né(e) le/en 13-06-1893 à New-York (Etats-Unis)

Grade soldat de 2e classe

Unité 2e régiment de marche du 1er régiment étranger

Classe 1914 (EV) Bureau de recrutement Bordeaux (33) Matricule au recrutement 997

John SMITH Mle 24613

Mort pour la France le 16-06-1915 (Souchez, 62 – Pas-de-Calais, France)

Disparu

Né(e) le/en 27-10-1885 à New-York (Etats-Unis)

Grade soldat de 2e classe

Unité 2e régiment de marche du 1er régiment étranger

Classe 1914 (EV) Bureau de recrutement La Rochelle (17) Matricule au recrutement 292